What Protest Art Means in the Age of Trump

Courtesy of Daniel Pagan

Well, we made it. It’s strange to feel relief that the president of the United States demonstrated enough restraint for 100 days to keep us from being wiped off the face of the planet. And yet here we are.

It’s incredibly exhausting keeping up with up with all the antics of the Trump administration: the executive orders, the travel bans, the health care bill, the wall, the deportations, the wire-tapping accusations, the dropping the biggest non-nuclear bomb ever, and all the other mistakes, lies, and transgressions.

But there is one aspect of our culture that does keep up in a way that news cannot—that holds a mirror to our politics while inviting thoughtful discussion about the issues at play: art.

Between the instant dissemination that the internet offers and the general sense of existential urgency Trump has invited, art has become an even more important part of political engagement. It has also helped countless people deal with the sense of utter shock and defeat that came with Trump’s election. That’s why we’re taking a moment to explore how politics has galvanized artists and how art—in this case, visual art—has been used as a means of resistance and protest during Trump’s first 100 days.

Courtesy of For Freedoms, Photograph by Wyatt Gallery

“I think if you look back in history, art has always been part of politics,” Wyatt Gallery, photographer and Executive Director of ForFreedoms told me over the phone recently. ForFreedoms is an arts Super PAC (yes, that kind of Super PAC) founded in 2016 that puts on exhibitions, hosts events, and collaborates with companies to bring visual art into the public sphere. On top of hosting workshops and designing billboards like the one above, ForFreedoms also features interactive art, inviting anyone, whether or not they call themselves artists, to contribute.

_________

“I think the election has been a wake up call for all of us that have previously been passive in the realm of politics.”

_________

“I think that when artists feel that the situation is more dire, and there’s more desperate need for action, then art becomes more prolific and you start seeing not only more artists, but more creative people, or individuals in general looking for ways to be involved, to have a voice, to make a difference, and to stand up for justice and for freedom,” Gallery told me.

PC: Bambi.

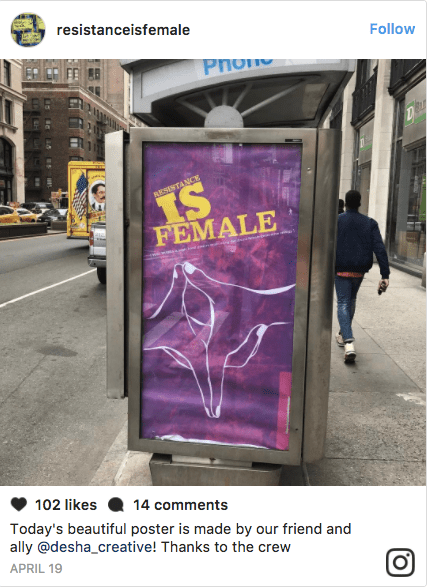

There has been a huge influx of resistance-themed art, whether it’s commentary on world leaders with the graffiti stylings of Mr. Dheo or Bambi (above) or the repurposing of spaces like phone booths as platforms for feminist messages, like the guerrilla campaign of Resistance is Female.

The participatory nature of much of this art—both as a result of the inherent accessibility of the internet and of art collectives—has provided a cathartic outlet for people whether or not they identify as artists.

“All of us were feeling like we were standing in a hall of mirrors and didn’t know which direction to turn,” Katina Papson Rigby, an organizer with 100 Days Action, told me.

100 Days Action is an arts non-profit that has engaged in a different kind of artistic resistance for every single day of Trump’s first 100 days as president. They crowdsourced ideas and organized film screenings, set up workshops, helped stage a Muslim pop-up prayer performance, and took up multiple residencies in various museums in the Bay Area. This weekend, they’re marking the end of their campaign (for now) with a dance party featuring DJs and music from the seven countries affected by Trump’s attempted Muslim travel ban.

They currently have an exhibition at San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Center for the Arts called 24 Hour Resistance, a conceptual but interactive “resistance gym” with seven stations including a “yoga for protest” section and a “tear duct warm-up station” in which you read the news while grating an onion. “We’re encouraging crying and accepting the sadness that is the news and really grounding yourself in your emotions,” Rigby explained.

“It’s artists coming together to support the voices of those who don’t get the attention they deserve and aren’t listened to,” she added. “We have the power to sort of chart a map for folks and navigate those conflicting messages and confusion that one might feel in a hall of mirrors.”

Courtesy of Daniel Pagan

“[Trump] is a singular person, but he is a tyrant and his decisions will affect the lives of millions of people all over the world. Art is vital because it serves as a window to the collective psyche. In a world where the powerful seek to ignore the masses out of greed, art can unify and make our voices heard.”

For Roxanne Jackson, a ceramics artist and professor, inspiration came partially from the paralyzing feeling of our new dystopian reality. But it was also inspired by the empowerment she felt marching in protest of Trump.

Jackson, whose own work explores the more grotesque and macabre aspects of death and transformation, spontaneously put a call out on Facebook for a Nasty Women art show. Hundreds of people swarmed the post, asking how they could help or submit their work. Jackson and several other artists and organizers like Jessamyn Fiore and Angel Bellaran, along with the help of volunteers, pulled off the first Nasty Women Exhibition in New York, which featured over 650 pieces of art. Proceeds from the show benefitted Planned Parenthood. But the show quickly ballooned into a global art movement, with Nasty Women Exhibitions continuing to be organized across the country as well as in the UK and the Netherlands.

It seems that art, particularly art in the name of resistance, is best when it forces us to confront the truth, whether it’s the grotesque nature of our president or the cognitive dissonance between our identities. “I absolutely think it’s important for artists to be the voices that challenge the status quo, that challenge injustices and bring them to light,” Jackson said.

Clearly, people have always felt a need to express themselves through art, but art needs us as well. It needs political engagement and reflection.

“I also think that in the United States the practice of making things in itself, no matter what the aesthetic is, is a political act,” Jackson said. “Because that is not something that is necessarily supported by the U.S. government.”

“Art is work,” Rigby said. “It’s not fluffy, it’s not easy, it doesn’t come at no cost. There’s very little value in some parts of society.” 100 Days Action was done with almost no funding, and as an educator Rigby has some well-founded fears about funding of the arts.

“If people do value the arts and appreciate the work that people do, our government and philanthropists need to put their money where their mouths are,” she said. “Because we create culture and we define culture, and it’s a matter of a survival for society.”

By Isha Aran.